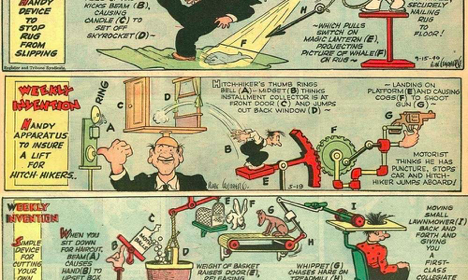

Rube Goldberg is Alive and Well in Architecture: What happened to elegant engineering?

Pulitzer Prize-winning American cartoonist, engineer, and inventor Rube Goldberg (Reuben Garrett Lucius Goldberg, 1883–1970) is best known for inventing convoluted machines to perform simple tasks. There is even an annual Rube Goldberg Machine Contest in which past challenges included simple tasks such as watering a plant (2011), hammering a nail (2013), opening an umbrella (2016), and turning off a light (2020).

Goldberg’s method is not “just for laffs.” Recent urban and architectural technology is distinctly rubegoldbergist. I challenge any architect to actually understand the mechanical systems which they are currently being convinced to install in their ceilings. I challenge them to actually know and understand the BIM elements they are inserting in Revit.

For example: What do the convolutions of an aluminum window frame actually accomplish? Why are they there and what was there before them? Does anyone understand the carpentry of a double hung window or know that two single-glazed double-hung windows have as good as or better energy performance than a double-glazed window twice their combine cost?

And what about shutters and curtains? Is it not true that they are simply excluded from energy calculations because Modernism forbids them? The idea that people are stupid and won’t use them is and that therefore they are incalculable is offensive supposition. To reduce energy rates, people close the curtains when needed.

The list for unnecessarily complex technology goes from kitchens to photovoltaics to freeways. Look at the typical kitchen cabinet hinge. Does it actually need to weigh half a pound and be composed of 13 parts? Worse, do we understand that intersections littered with traffic lights and traffic signage exhibit the same faulty engineering?

Who in the world is aware that PV panels pump 80% of the energy received from the sun as heat, right back into the atmosphere? Who actually realizes that, if there are enough of them in one place, PV panels create heat islands? What happened to “less is more” in design? What happened to elegant engineering?1

Worldwide, buildings and the construction sector account for around 39% of carbon dioxide emissions released from energy use and industry.Cement alone releases 8% of the world’s global carbon emissions each year. We use untold amounts of energy to, first, extract steel, glass, aluminum and concrete, and then we air-condition and heat the bejesus out of the resultant buildings. Meanwhile, their so-called green architecture doesn’t even come close to the performance of traditional buildings.2

China already builds two billion m2 of new floor space each year. With almost half of the world’s construction taking place in China in the coming decade, that is where the construction materials opera will play out on the grandest scale.From 2001 to 2016, the primary energy consumption in China’s building sector more than doubled, reaching the equivalent of just under a billion tons of coal.3

The carbon cost of constructing buildings in the first place, including the raw materials and energy used throughout the supply chain, makes up around a third to a quarter of China’s energy bill, and one fifth of China’s carbon emissions.In 2015, China’s emissions from construction, including the extraction and processing of raw materials—steel, cement, iron, and aluminum—was equivalent to burning one billion tons of coal.

Laid out over a single story, China’s annual two billion m2 of new floor space could cover 1.3 times the size of the entire footprint of London.4 But at 5 stories it would be ¼ of London’s footprint—and very pleasant. Indeed, in 2017, China set a goal to have 50% of all its new urban buildings certified as green by the end of 2020. But as China asks itself how it will go about this enormous task, we ask, is China being misled?

While there is some consciousness in China about a movement to make its buildings more sustainable, it seems to be adopting the worldwide fashion to become “greener” à la Rube Goldberg. One way is by covering buildings with vegetation and trees. Another is by recycling potentially toxic industrial waste in 3-D printing. Another is the continued application of glass curtain walls, and yet another is hoping that high-tech will save them somehow.

Despite knowing that Nature is stronger than mankind, that holding water in buildings risks destructive leaks, that maintaining plants in them is notoriously costly, and that plant roots and limbs can do untold damage to buildings, architects are now adding to those risks the risks of branches or trunks—even potted trunks—flying at 100 mph in a typhoon, at a height of ten stories above ground level.

What are these preachers of high-tech preaching? Building greenery into buildings, in the manner that they are proposing, is a 1970s idea that was bad then, and ludicrous now. Yes, we can build it, but that is no reason we should. The idea that building greenery into high-rises maximizes the opportunity for forests in urban areas is an urban myth, if not an outright lie.

China already has a great tree-planting program in its cities, that follows three classic planning street rules–- plant lots of trees, plant lots of trees, and plant lots of trees. The appeal of creating forests in dense urban areas is obvious, but the only non-rubegoldberg-ist way it will work is to follow Classic Planning Town and Country rules.

For starters, high-rise construction is not equal to density. Take the building in the image here and lay it down and you will get 4-6 stories of urban fabric that is quite pleasant. There will be plenty of space left over for an urban forest on the ground. Who are they kidding?

We should improve the microclimate and biodiversity on the ground where they belong, not in the air where we pay a premium to suspend them on steel, glass, and concrete. Indeed, we have many tools nowadays to reduce the production of CO2, and the most efficient mechanism for that is vegetation. But paying to suspend trees in the air seems more like a gimmick than a durable solution. Has that architect ever trimmed a 50-year old tree?

Is this project “cool?” Yes. But do you really think that the luminaries who came up with these systems will help take us off today’s fun ride to environmental doom? Is this supposed allocation of resources desirable? No. If the architects aren’t building for 50 years, their work is patently unsustainable. Their clients should not pay for such a poor product.

Who other than the owner and the social controller of the property benefits from a building with “sky garden balconies” that exempt green spaces from a building’s calculated plot ratio? Everyone knows they will be abandoned and built on. Not having high-rises is organic. Pasting greenery on high-rises is inorganic. Why the fairy tale?

3D printing is another myth we are promoting for construction. While 3D printing would allow speedier assembly, fewer laborers, and it could potentially minimize construction waste, does it really make for a better future?

Why remove the human hand? As mentioned in The Art of Classic Planning, hand work is essential for human wellbeing, and massive construction projects may in fact be our way out of this difficult time. The savings with 3D-printing technology benefits only the owners of that technology, not the users or buildings or the people in the street on which they stand. Certainly not the construction worker. Definitely not the community.

But worse than that is the idea of using solid wastes sourced from steel mills, coal plants, and urban construction sites. Sorting them, granulating them and processing them into the ink that feeds the 3D printer almost guarantees the increased presence of heavy meals in the built environment. Where is the proof of their absence? And while the world is running out of sand, such systems rely on it, no less than conventional concrete does. So where is the improvement?5

In its quest for progress, Western society is, to its detriment, subsidizing certain technologies and methods over others, and China is following suit in blind imitation. Worse, with steel mill wastes making up to 60% of the building “ink,” China may not only be poisoning itself but re-poisoning its people and places.

No, there is nothing progressive about glass curtain walls. They have been an architectural fashion for 100 years. In the US, the Gulf States, and even in China, the proclaim nothing more than Modernism’s reliance on cheap energy—and the presence of huge government energy subsidies. Everywhere else curtain walls express dreary consumerism. Their reflectivity is sold on the myth of their transparency. Is there any other field in which the Emperor’s clothes are more obvious?

If China insists on an illusion that will expire like bad milk in the heat, it is their choice. But other places, where there is still a measure of common sense should reconsider the false promises of so-called “green” but in fact over-complicated devices and systems. Architects can no longer hide behind their mechanical or structural engineers. They have to fully understand and know what they are putting into their buildings.

Creating new floor surfaces with recycled pieces of old glass is old-hat. Building exterior retaining walls of “rip-rap,” chunks of old cement collected from demolished structures, has been done since concrete was invented 2,000 years ago. Today, anyone considering a “curtain wall” as an important energy efficiency renovation is likely fooling only themselves. It is not only the heat gain on a building, but how that heat moves around. And then there is the matter of fresh air and air changes. Has anyone recently thought of simply opening a window?

Just as in the fountains of Rome water flowed from its natural sources, through them, and drained directly into the Tiber without stopping, atmospheric air should, in most cases, flow directly through buildings for their ventilation. Net Positive Toronto Mechanical Engineer Jack Laken says that heating, cooling, humidifying, desiccating, and filtering air should in most cases be necessary only in highly specialized environments like operating theaters, clean rooms, and food plants. If the external air is not good enough to breathe, the place is not good enough to inhabit.

Thank normal people for the slow acceptance of novelty. Passive design, heating or cooling a building without mechanical means, has been done for thousands of years. Indeed, when it comes to habitation comfort heating in deserts in winter often requires more energy than cooling them in summer might need. Traditional Baghdadi, Damascene, Cairene and Pakistani townhouses all had substantial elements that provided comfort in summer and winter. Many “passive designs,” which use no fuel for heating or cooling, already exist in China’s traditional houses.6

Sometimes, taking vernacular ideas and expanding on them for energy-efficient public buildings is a good way to start, as Beijing-based architect Dong Mei has been doing in her exploration of daylighting. The problem with “green” solutions isn’t resistance to something different and new, but that they are simply inadequate when out of context. When a vernacular-type “daylighting solution” requires more Jetsons hardware for mechanical shading, it is simply yet another system for a client to purchase and manage.

But in the traditional Chinese courtyard houses, temperatures are regulated without any mechanical means. In these houses, warm air rises through a tall space and draws a draught of cooler air in below.

Indeed, the designs of the past have all the inspiration we need. The benefits of modern science lie not in technology and so-called innovative architecture. It lies in understanding the mechanics and physics of the traditional solutions, and then tweaking them for a slightly higher performance. As we are rapidly learning, the cultural context is of significance too. A culture in which people go to the beach or the mountains for summer vacation requires less air-conditioning in summer.

As of the end of 2018, China had more than 10,000 architectural projects certified as “green.” But what does that really mean? While the Amazon rainforest burns into oblivion for corporate benefit, the same or similar corporations on the other side of the world are selling “vertical forests” in places like Nanjing, formerly a major center of Chinese culture.7

And while the vertical forests of Nanjing are expected to absorb in a year about as much CO2 as 10 round-trip flights from Beijing to London, it will take a lot more to make a dent in the carbon emissions of China’s construction industry. Indeed, the breakneck development and profiting from the demolition of homes and workforce relocation has removed neighborhoods all over the country with little regard to their urban value or sense.8

Everyone loves the poetics of a green vertical forest. But maybe now is the time to consider “what works,” “what’s good for the people,” and leave Rube Goldberg out of the equation.

End Notes:

- Greg A. Barron-Gafford, Rebecca L. Minor, Nathan A. Allen, Alex D. Cronin, Adria E. Brooks and Mitchell A. Pavao-Zuckerman, The Photovoltaic Heat Island Effect: Larger solar power plants increase local temperatures, Scientific Reports vol. 6 (Website), 13 October 2016.

- IEA, Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction 2019, IEA, Paris, December 2019. See also: Lucy Rodgers, Climate change: The massive CO2 emitter you may not know about, BBC News (Website), 17 December 2018.

- Tengfei Huo et al., “China’s energy consumption in the building sector: A Statistical Yearbook-Energy Balance Sheet based splitting method,” Journal of cleaner production 185 (2018): 665-679. See also: Cici Zhang, The country building a ‘new London’ every year: With half of the world’s new buildings to be constructed in China – how can it build them better?, BBC.com (Website), 11th June 2020.

- Cici Zhang, The country building a ‘new London’ every year: With half of the world’s new buildings to be constructed in China – how can it build them better?, BBC.com (Website), 11th June 2020.

- Vince Beiser, Why the world is running out of sand, BBC Future (Website), 17 November 2019.

- Wei-Ju Wang and Ming-Hung Wang, “Embedded schema: Towards a new research program of traditional Chinese house types,” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 7.1 (2008): 1-7. See also: Xiang-xiang GAO et al., “Research on winter indoor thermal environment of courtyard house with Chinese Kang in the North China,” Building Science 2 (2010). Also: S. Chang,The spatial organisation and socio-cultural basis of traditional courtyard houses, Diss., University of Edinburgh, 1986.; Donia Zhang, “Courtyard houses of Beijing: lessons from the renewal,” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review (2015): 69-82.; Chien-Wei Chiou and Huey-Jiun Wang, “Damage to Chinese courtyard houses during the September 21, 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake in Taiwan,” Journal of Earthquake Engineering 15.5 (2011): 711-723.; Werner Blaser, Courtyard house in China: tradition and present, Birkhauser, 1995.; Y. U. A. N. Shi, “Wind Environment Characteristics in Chinese Vernacular Courtyard and Its Design Application,” Cutting Edge: 47th International Conference of the Architectural Association, 2013.; Donia Zhang, “Classical courtyard houses of Beijing: architecture as cultural artifact,” Space and Communication 1.1 (2015): 47-68.; Fatma Abass, Lokman Hakim Ismail and Mohmed Solla, “A review of courtyard house: history evolution forms, and functions,” (2006). And: Gregory Byrne Bracken, The Shanghai alleyway house: a vanishing urban vernacular, Routledge, 2013.

- Lauren Teixeira, Why Is Nanjing Demolishing Its Last Historic Neighborhood?, SupChina (Website), 18 July 2017.

- Lauren Teixeira, Why Is Nanjing Demolishing Its Last Historic Neighborhood?, SupChina (Website), 18 July 2017.

[Classic Planning is a registered trademark of the Nir Buras Entities.]

WELCOME!

Get In Touch

Please get in touch with us

to discuss your requirements.

Please get in touch with us

to discuss your requirements.