The Art of Making Books: The artisanship of 2K/DENMARK and Graphicom in

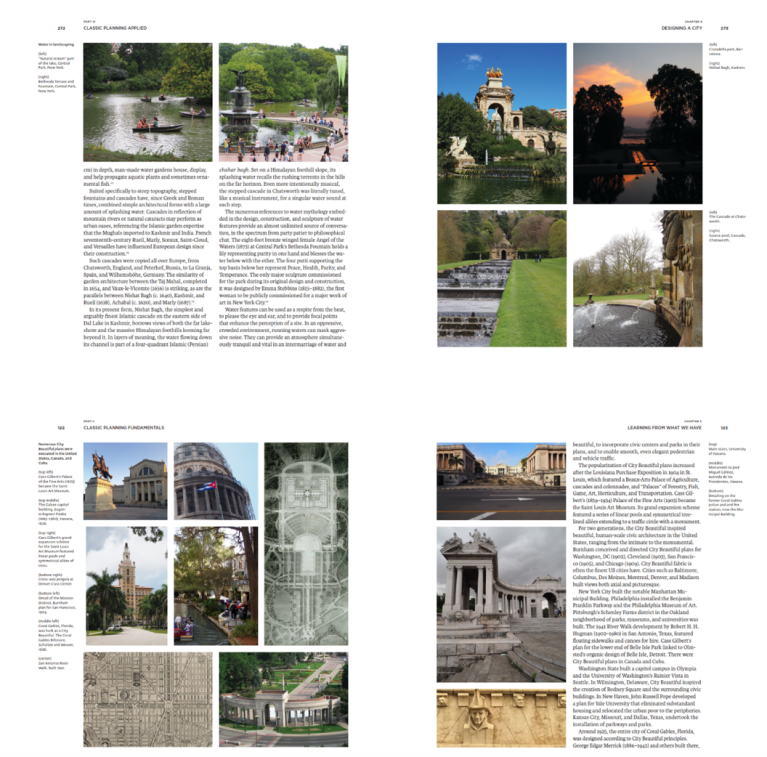

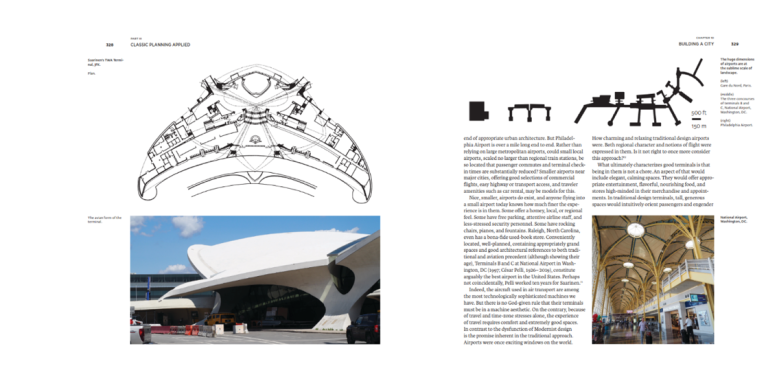

producing my book, The Art of Classic Planning

and one who works with their hands, their mind, and their heart is an artist.

Indeed, Webster 1828 defines artisan as “someone skilled in the

practices of a mechanic art or craft”, while an artist is “one who

professes and practices an art in which science and taste preside

over the manual execution.” So, by these definitions, pretty much

all artists areartisans. Meanwhile, the work of some artisans

contains so much aesthetic, intellectual, sensual, and spiritual

content, that they can be considered artists as well.

2K/DENMARK in Aarhus, Denmark, are artists; and their

medium is books. I am so fortunate that Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press chose them to design and print

my book, my book, The Art of Classic Planning.

The Tactile Enjoyment of Books Makes Them a Cutting-Edge Knowledge and

Learning Technology

together by a cover.

holding an authentic, genuine printed book—turning the pages, physically holding in your hands the thoughts, ideas, images, and

emotions that an author has created. A mathematician would call it a beautiful solution.

Our curiosity is satisfied by turning the pages, flipping back to reread parts, skipping ahead to search for something, or holding in

place a finger while reading another section. Feeling the smoothness of a dust jacket with our fingers, gently winding a silky

bookmark ribbon around them, or pulling up a translucent parchment protector to reveal a precious image is magical.

knowledge and creativity. Their physical features are related to understanding their texts. Contrary to current popular fashion, it can be

argued that books are still better for teaching students how to read closely and discuss what they’ve found. They can markup the text

and simultaneously search through multiple pages. An entire class can readily turn to the same page for discussion. Students can

literally feel a beginning, a middle, and end.

reader feels convinced that there were actual illustrations within the book—instead of the reality that the scenes resided solely in their

own imaginations.

Reading Research is in its Infancy

linguistic mechanics of reading. We believe that new

technology can supplant books because we are simply

unaware of how reading actually works. Indeed, the majority

of reading research is focused on dysfunction such as

dyslexia—even though, while important, it affects only roughly

10% of the population.

revealing that linguistic and non-linguistic processing occur

along a spectrum, from the visual recognition of letters, to comprehension at the levels of discourse and articulation.

Advances in brain imaging like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have discovered that the brain has no dedicated “reading center.” Instead, reading is mapped to left-hemisphere neural areas that are believed to serve articulation, word analysis, and a “word-form area.” This part of the brain is believed to be responsible for the rapid, automatic, and fluent identification of words.

While learning to read, we transform some of the visual structures of the brain into a specialized interface between vision and language. As readers mature, and the “word-form” area of the brain develops, rendering the design of fonts, text, paragraphs and book pages even more essential to quick comprehension.

Symbols of Social Enlightenment, Learning, and Tolerance

which can greatly contribute to the book’s intellectual and emotional impact. People turn to printed books for the emotional

experience of receiving what the book has to offer through the book’s physical medium. It’s difficult to imagine a similar level of

engagement with a digital text.

global symbols of social enlightenment, learning, and tolerance. They are a common physical package that we proudly retain, archive,

and display. Book lovers love to display what they’ve read and decorate their homes with their collections.

people younger than 44. Additionally, 75% of people in the US aged 18 to 29 said in 2017 that they had read a physical book, higher

than the average of 67%.

associated with books. Books also satisfy the need to escape the increasingly ubiquitous glow from a screen. They feed the soul,

which is why so many fear-based regimes opt to limit or destroy them.

As cultural objects, the future of books is thus inseparable from the role of culture itself. But while the book as a product is a simple

technology, its production is anything but simple.

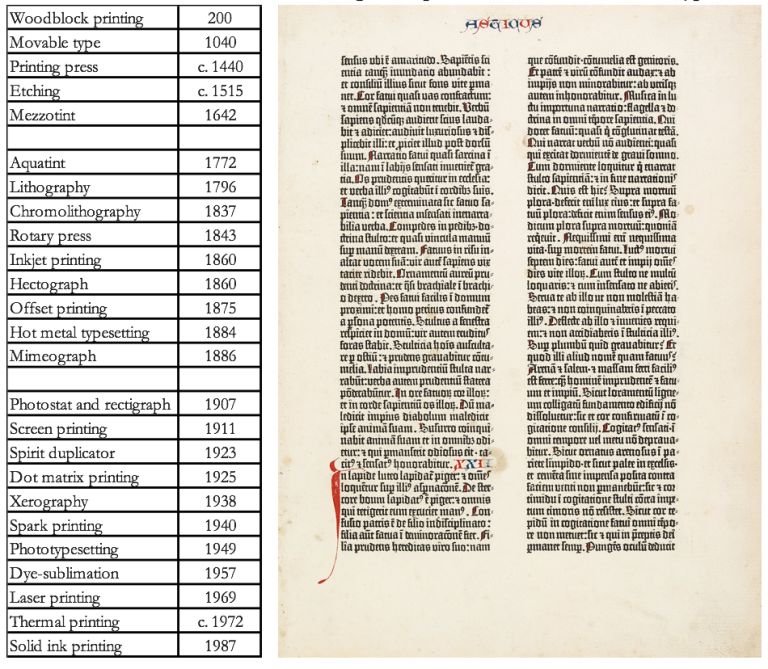

Printing Books is a Defining Invention of Civilization

Printing books started in Tang Dynasty China (618-907 CE), with the oldest surviving printed book being the 868 CE Diamond Sutra. Movable-type printing using fired clay fonts was also first invented in China in 1041-1048 CE, and the world’s oldest existing book printed with movable metal type is the Korean Jikji of 1377. In Germany, Johannes Gutenberg improved the method of movable type printing around 1440, and in 1455 he published The Gutenberg Bible in Latin.

In 1455, there were no printing presses in Europe yet. But when they came on the scene, no previous invention in human history had spread so far, so fast. By 1500, over 20 million books had been printed–one for every five people living in Western Europe.

substantially improved upon until the 1820s, with the

introduction of steam printing presses and paper mills. As a

result, the number of books increased so considerably, that

virtually none of the world we know today would have been

possible without books. As of 2010, 130 million individual

titles had been cumulatively published, and annually, about

200 million books are printed.

breakthrough technologies, including paper, the printing press, and electricity. Each technology is in turn reliant on other breakthrough technologies.

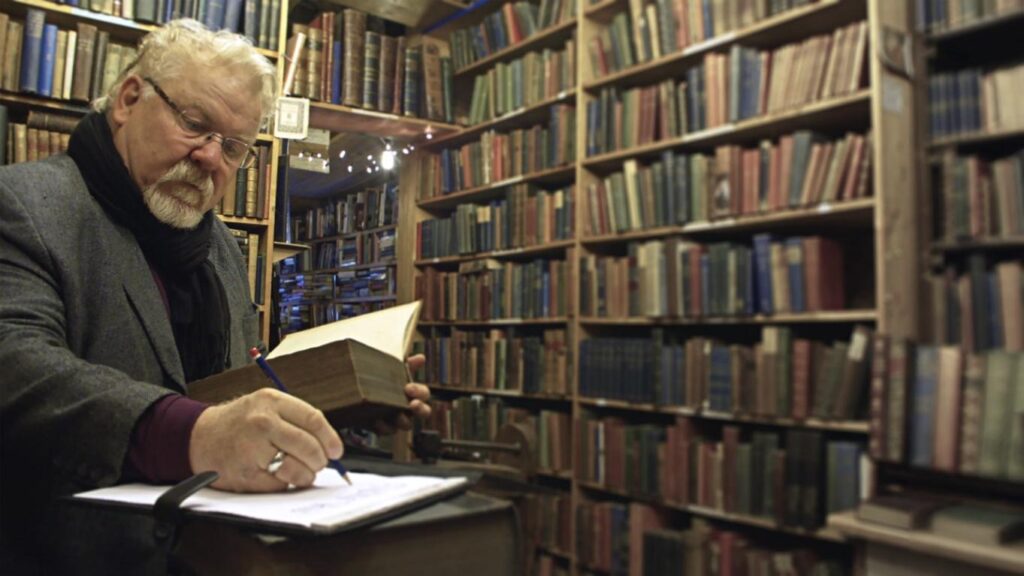

designer of the book Klaus Krogh of 2K/DENMARK, and the book’s printer, Antonio Zanella of Graphicom in Italy.

Typeface and Book Design: the intersection of Technology, Biometrics and Neurobiology

2K/DENMARK specialize predominately in the design of Bibles, but they also design and typeset elaborately illustrated and key texts such as The Art of Classic Planning. Among the countless books Krogh and 2K/ design each year are 200 Bibles they produce annually, including a recent annotated version with 60,000 reference notes.

software developers, turned type designers,” Krogh and 2K/

can take a year to design a font family—and they have

designed thousands over the years. As a type foundry, 2K’s

ambition is to fuse form and content into a pleasant book

you could have on your desk, on a coffee table, or read under

a blanket on a snowy day. Their goal is to create books that

you not only experience with your eyes, but also as objects

you hold in your hands.

Krogh loves letter shapes, and has always been intrigued by such things as “why an ‘s’ looks like a snake.” He designed his first

typeface at age 13, trying to write “Bob Dylan” on the wall of his bedroom.

impacted design and thinking. His interest lies in how the shifts that came with changes in printing technology influenced the design

of typefaces. Krogh just finished studying the period of 1840 to 1860, when large modern printing machines were invented.

legibility. “Books are containers of what’s important, difficult, and holy that we carry through space and time,” says Krogh. “They are

the most useful and practical form of transferring information, the best technology for learning, information, and knowledge,” he says.

cycles of gradual improvement in typographic quality are repeatedly interrupted by a sudden decline, followed by a subsequent slow improvement corresponding to the introduction of new technologies. In other words, in the immediate wake of the introduction of a

new technology, typographic quality often suffers—requiring new practitioners to train in old practice. As MIT scholar Sherry Turkle

said: “We do not err as a society when we innovate, but when we ignore what we disrupt or diminish while innovating.”

is improving, there is a renewed appreciation of the additional values inherent in printed books—not unlike the recent resurgence

of the popularity of music on vinyl.

different tasks. Though publishing may be perceived as being transformed by digital technologies, its inherent qualities are still not as effective as those of the printed page.

The reading brain is develops distinctively and intricately, leveraging the pattern constructions of letterforms, phonemes, and words to interpret written text.

explains. But a typographic designer is also a steward of the readability of the text at the paragraph and page levels. Variables such as

line length, line spacing, justification, indentation, line breaks, margins, gutter, and general white space all contribute to the readability

of a printed page.

Here too, the brain relies on known patterns and past experiences to process the text. If the designer strays too far from what the well-trodden neural pathways can and will recognize, the brain becomes distracted and comprehension diminishes. Indeed, certain typographic styles are associated with certain types of documents, and readers’ perceptions are influenced by how well those conventions are followed. To belong to a genre, a document must trigger appropriate expectations, effectively conforming to a set of rules or expectations.

Devoted typeface designers such as Krogh tend to think that the part of the brain used in reading has not entirely forgotten its pre-literate function. They are convinced that the face of the text still speaks and plays its part in the decoding and comprehension of the letterforms. “Typeface expression” might not be a scientifically robust term yet, but there is no doubt that a typeface can make words smile, frown, scream, or sing. And ultimately, “we design the quality of the typeface to match the content, concludes Krogh.” Functional typography visualizes the content before it is read.

I asked Krogh what makes a good book, and responds “that what it looks like says a lot about what the content of the book is.”

What the internet has changed, says Krogh, is our relationship to information itself. “With the Internet growing, there is too much of it and it is too difficult to find. The internet is becoming a battleground where you can’t verify information, so you can’t be sure of its provenance. The Internet is becoming its own enemy. You can find anything, but you can’t know its reliability,” he says.

“Conducting” Technology to Print Beautiful Books

While Klaus Krogh and 2K/ arrange the “music” of a text into a beautiful score, Antonio Zanella of Graphicom is the “conductor” who elevates the score into a symphony of sensual reality. A notably modest man, Antonio Zanella relates that he started in mechanical engineering, went on to sales, and then began working in 1986 as a print broker. Aiming primarily at the European market for illustrated books, from the very beginning, he specialized in high-quality projects before joining Graphicom.

For many, printing quality was merely a technical challenge. But decades of serving the complex requests of clients such as major museums and art galleries, top publishers, and leading advertising agencies around the world led Zanella to conclude that sensitivity, communication, promptness, precision, and flexibility were as important as cutting-edge technology.

Since Zanella uses the same machines that other printers also employ, the extraordinary quality of work he produces exemplifies book manufacturing as an artform. Zanella challenges himself to wield the latest technology in the service of the highest quality craftsmanship.

Graphicom, one of only a handful of such printing houses in Italy—and possibly the world—serves high-standard clientele. They collaborate with important publishers in the UK, Germany, France, Scandinavia, Switzerland, and the US, to print some 500 titles annually. “I am interested in working for good galleries, museums, and customers who constantly push us to improve,” says Zanella. “We love the particularly difficult technical challenges,” he says. “We print the impossible!”

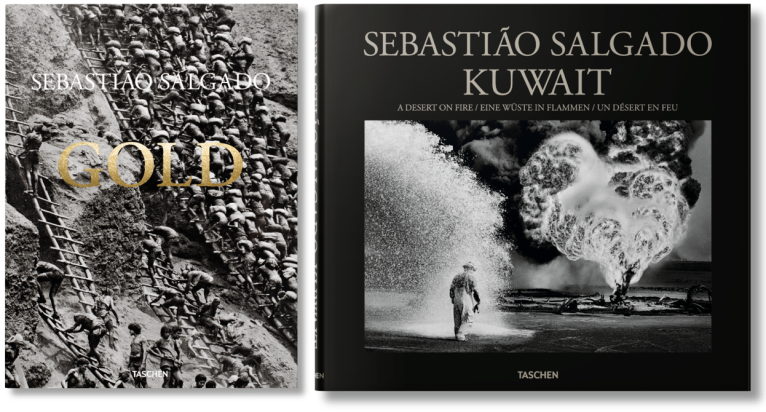

A recent example was the unexpected challenge of printing a true black and white. Surprisingly, a genuine deep black is the hardest color to attain in current printing technology, explains Zanella. He is particularly proud of two black-and-white books of Sebastiao Salgado’s photographs that Graphicom printed, Gold and Kuwait. The first is about a gold mine in Brazil. The other is about the firemen who helped put out the oil field fires after the war in Kuwait in the early 90’s. “It’s probably the best book we printed… Whatever the challenge, I continue to learn,” says Zanella.

It is not by accident that Graphicom is based in Italy and specifically in Vicenza. “Italian individualism,” says Zanella, “is at the heart of the typically small Italian businesses, which contrast with the large companies of Germany, for instance… Vicenza itself is famous for its gold industry, tanneries, and mechanical work,” he explains. “These are all crafts that require a great deal of expertise to produce really top products.

Workers in Italy stay with their companies sometimes their whole lives, bringing with them the experience and expertise that wise management like Zanella’s can direct toward profitable, high-quality work. The small size of the companies makes them especially nimble when competing in the worldwide market. “And small also means human-scale and less stress,” says Zanella. “Big names come to us for our better service,” he says.

As for the future of printing, Zanella does not see it as digital, at least for perhaps10 more years. “Ten years ago they promised it would be here now—but it isn’t yet,” he says. “There will always be a market for quality work.”

Zanella himself reads books and has about 2,000 of his own, organized by topic, and “taking up too much space in the house.” His favorites are the nearly 500 novels of Georges Simenon, best known as the creator of the fictional detective Maigret.

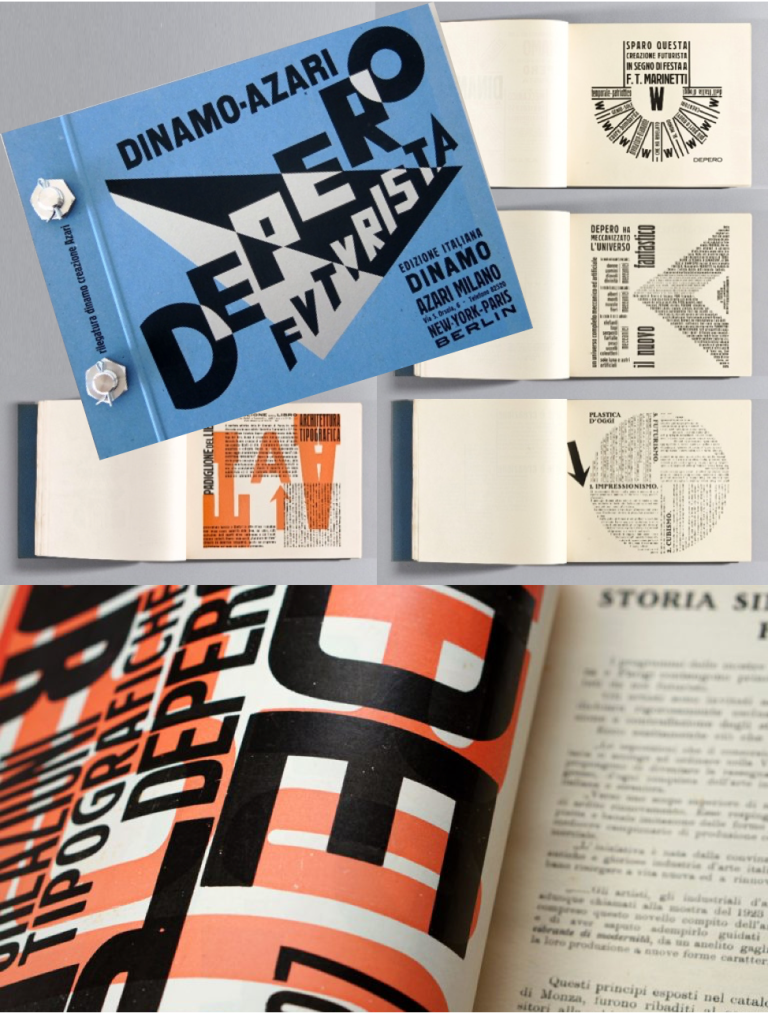

What’s the favorite book you produced?” I ask Zanella. “An exact copy of Italian Futurist Fortunato Depero’s ‘bolted book,’ Depero Futurista (1927, 2017),” he responds. Clearly unique, two large industrial aluminum bolts secure this portable portfolio of Depero’s paintings, sculptures, designs, advertising, and literary work. Literally fitting Zanella’s mechanical and book manufacturing interests, the bolted book is considered a masterpiece of graphic design, typography, and bookmaking.

Libros habeo, ergo sum

The most worthless book of a bygone day is a record worthy of preservation; like a telescopic star, its obscurity may render it unavailable for most purposes; but it serves, in hands which know how to use it, to determine the places of more important bodies.

– Augustus De Morgan in 1847, among the founders of University College London.

As technologies advance, we must nonetheless maintain access to the knowledgebases of old for use in future endeavors. The study of our intellectual history since Gutenberg depends on our incorporating this point into our plans for this century. And leading such endeavors today are media artist/artisans like those who designed and produced my book for the Belknap Press at Harvard University Press, Klaus Erik Krogh of 2K/DENMARK and Antonio Zanella of Graphicom,.

In 2010 I gave into “the times” and let the idea of digitization overwhelm my thinking. I decided to try to see what life without books would be like, and I gave up all but my 100 favorite books back in 2010. Now I am rebuilding my library and I have purchased another 200, so my library is once more growing. I need books around me. Libros habeo, ergo sum. I have books, therefore I am.

End Notes:

[i] Webb, Patrick, The Spirit of Craftsmanship (Personal Correspondence), 12 November 2019.

[ii] Webb, Patrick, The Spirit of Craftsmanship (Personal Correspondence), 12 November 2019.

[iii] Webster 1828; 1913. Webster, Noah, Noah Webster’s first edition of an American dictionary of the English language. 1828, 10th ed. Foundation for American Christian Education, San Francisco, 1998. The OED defines artisan as a worker in a skilled trade, especially one that involves making things manually. It defines artist as a person who creates paintings or drawings as a profession or hobby; or as a person who practises or performs creative arts, such as a sculpture, film-making, acting, or dancing.

[iiii] Buras, Nir Haim. The Art of Classic Planning: Building Beautiful and Enduring Communities. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020. https://uvamagazine.org/articles/whats_the_future_of_books_in_a_digital_world/

[iv] The technical term for a stack of printed pages, bound along one side, and held together by a cover is a “codex,” from the Latin caudex, meaning “tree trunk”, “wood block”, or “book”, plural codices. Today, the term “codex” usually refers only to manuscript books with hand-written contents, but it still describes the near-universal format for printed books in the Western world.The compactness, sturdiness, economic use of both sides, and the ease of reference that random access affords books caused books to gradually replace scrolls from the first century CE on. By the 6th century, books completely replaced scrolls throughout the Christianized Greco-Roman world. Sadokierski, Zoë, What is a book in the digital age?, The Conversation US (website), 11 November 2013. http://theconversation.com/what-is-a-book-in-the-digital-age-19071. Roberts, Colin H.; Skeat, Theodore Cressy, The Birth of the Codex, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1983, pp. 1, 75; Lyons, M., Books: A Living History, Thames & Hudson, London, 2011, pp. 8. 45-53.

[v] Knight, Donna, Savoring the magic of the printed page, The Courier, Houma LA, 24 Nov 2019. https://www.houmatoday.com/news/20191124/donna-knight-savoring-magic-of-printed-page

[vi] Dirda, Michael, Dirda on Books, Book World Section, Washington Post, Washington, DC, 2 May 2002.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Haahr, Johs Krejberg, TypeFacial expression—text that smiles, 2kdenmark.com (website), Aarhus, DK, 6 June 2018. https://stories.2kdenmark.com/typefacial-expression-text-that-smiles-6afe2b8cb909; Shaywitz, S., & Shaywitz, B. (2008). Paying attention to reading: The neurobiology of reading and dyslexia. Development and Psychopathology, 20(4), 1329-1349; Shaywitz, Sally, Overcoming Dyslexia: A New and Complete Science-Based Program for Reading Problems at Any Level, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2003, p. 78; Stein, J. “The neurobiology of reading difficulties.” Prostaglandins Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 63.1 (2000): 109

[ix] Tanselle, G. Thomas, Texts and Artifacts in the Electronic Era, 21st C, 3.2, 1998.

[x] Das, Subhamoy, Importance of Books in Today’s World of Instant Knowledge, Medium.com (Website). 23 April 2015. https://medium.com/@subho/importance-of-books-in-today-s-world-of-instant-knowledge-31a63c227f9.

[1xi Handley, Lucy, Physical books still outsell e-books — and here’s why, CNBC.com (Website), 19 September 2019. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/09/19/physical-books-still-outsell-e-books-and-heres-why.html.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] McDermott, Joseph P., A social history of the Chinese book: Books and literati culture in late imperial China. Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong, 2006, pp. 10–11; N.A., The Invention of Woodblock Printing in the Tang (618–906) and Song (960–1279) Dynasties, Asian Art Museum (website), San Francisco, N.d., https://education.asianart.org/explore-resources/background-information/invention-woodblock-printing-tang-618%e2%80%93906-and-song-960%e2%80%931279; N.A., Pi Sheng’s system for movable type, silk-road.com (website), N.D.; both accessed 30 November, 2019; Unesco, Baegun hwasang chorok buljo jikji simche yojeol (vol.II), the second volume of “Anthology of Great Buddhist Priests’ Zen Teachings”, Memory of the World, Unesco (website), N.D. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/memory-of-the-world/register/full-list-of-registered-heritage/registered-heritage-page-1/baegun-hwasang-chorok-buljo-jikji-simche-yojeol-volii-the-second-volume-of-anthology-of-great-buddhist-priests-zen-teachings/; Kim Jong-myung, Jikji: An Invaluable Text of Buddhism, The Korea Times, Seoul, 1 April 2010. http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/culture/2015/10/293_63447.html

[xv] Gutenberg’s many contributions to printing include mass-producing movable type; oil-based ink; adjustable molds; mechanical movable type; and the use of a wooden printing press similar to the agricultural screw presses of the period.

[xvi] Haley, Allan. Typographic milestones. John Wiley & Sons, 1992; Haley, Allan, Gutenberg’s Invention, Fonts and Typography, https://www.fonts.com/content/learning/fontology/level-4/influential-personalities/gutenbergs-invention; https://cdncms.fonts.net/documents/b8ae325725574836/Fontology_GutenbergsInvention.pdf; Whipps, Heather, How Gutenberg Changed the World, livescience.com (Website), 26 May 2008, https://www.livescience.com/2569-gutenberg-changed-world.html

[xvii] The 1999 A&E Network People of the Millennium countdown ranked Gutenberg as no. 1. Time–Life magazine in 1997 and The Wall Street Journal in 1999 named Gutenberg’s invention of movable type printing as the most impactful event of the second millennium. https://wmich.edu/mus-gened/mus150/biography100.html; Drucker, Peter, The Millennium’s Most Influential Innovations, The Wall Street Journal, New York, 11 January 1999, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB915764828134990000; https://web.archive.org/web/20100310192514/http:/www.mainz.de/gutenberg/g2000.htm; Gottlieb, Agnes H. 1000 Years, 1000 People: Ranking the Men and Women Who Shaped the Millennium. New York: Kodansha International, 1998; The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, Gutenberg Bible, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 27 January 2016, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Gutenberg-Bible, accessed 30 November 2019; Taycher, Leonid, Books of the world, stand up and be counted! All 129,864,880 of you, Booksearch.blogspot.com (Website), 05 August 2010. http://booksearch.blogspot.com/2010/08/books-of-world-stand-up-and-be-counted.html

[xviii] Fallows, James, The List, in The 50 Greatest Breakthroughs Since the Wheel, The Atlantic, November 2013. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2013/11/innovations-list/309536/#list. 1. The printing press (1440s); 2. Electricity (late 19th cent.); 3. Penicillin (1928); 4. Semiconductors (mid-20th cent.); 5. Optical lenses (13th cent.); 6. Paper (2nd cent.); 7. The internal combustion engine, late 19th cent.); 8. Vaccination (1796); 9. The Internet, (1980s); 10. The steam engine, (1698-1712).

[xix] Turkle, Sherry, cited in Wolf, Maryanne. Skim reading is the new normal. The effect on society is profound, The Guardian, 25 August, 2018.

[xx] Sadokierski, 2013.

[xxi] Krogh, Klaus E., & Haahr, Johs Krejberg, The Twofold Task of Typography, 2K/DENMARK, Aarhus, 5 November 2018, https://stories.2kdenmark.com/the-twofold-task-of-typography-b522650a5ae1.

[xxii] Krogh & Haahr, 2018,

[xxiii] Haahr, 2018.

[xxiv] N.A., De Morgan, Augustus,Encyclopaedia Britannica, New York, 1910.

[xxv] Tanselle, 1998; Buras, Nir, Man-Machine Rules, Mad Scientist Blog #106, Mad Scientist Laboratory (website), US Army Training and Doctrine Command, 17 December 2018, https://madsciblog.tradoc.army.mil/106-man-machine-rules/.

WELCOME!

Get In Touch

Please get in touch with us

to discuss your requirements.

Please get in touch with us

to discuss your requirements.