The Case for Classic Streets

Note: The author has nothing personal against swine. On the contrary, he recognizes them as intelligent and adaptable.

Even when masquerading as “complete streets,” contemporary traffic engineering “manages” traffic by wastefully segregating it into lanes, degrading the urban fabric around with markings, signals, and signage, and producing outright no-man’s-lands.

There is nothing wrong with cars per se. They are, after all, useful tools. But the “original sin” of planners and engineers was thinking that technology could solve people problems. Paradoxically, while striving to attain the most efficient flow of cars feasible, most traffic elements are designed to slow, if not stop them.

While pedestrians are made to detour and stand at crosswalks for a turn to cross a street, drivers are encouraged to barrel down streets at 40 mph (60 kph) with a false sense of security, to behave as if they have no responsibility to look out for others.Meanwhile, pedestrians are lucky if they are not run over by bicyclists on bike lanes. There are annually some 36,000 motor vehicle fatalities in the United States. Over 1.35 million are killed worldwide—one for every fifty people born each week. Traffic kills two to four times the number of people killed annually by terrorism and war.1

The Failure of Modernist Traffic Planning

Back in 1900, one person a day was killed on the streets of New York City. Half the fatalities were due to trolleys, the rest by horse-drawn wagons, automobiles, runaway horses, and bicycles. In the effort to make streets safer, quadrillions were spent on road widening, signage, pavement markings, signals, and one-way streets. The result is that fatalities were reduced by 50–60 percent.

But given that trolleys contributed half the fatalities to begin with, all the efforts and expenditure brought little benefit. That is not much to show for traffic engineering, a technological discipline promising efficiency while proclaiming that the only approach to street safety is theirs.2

Someone who has long recognized this is University of Virginia associate professor and member of the Center for Transportation Studies, Peter Norton. Teaching history, ethics, and social dimensions of technology, Norton’s research includes “smart” buildings and cities, environment, infrastructure, and transportation. He has written prize-winning articles about science, technology, transportation policy, traffic safety, and autonomous vehicles and won awards for his research and teaching dedication and excellence.

Most notably, Peter is the author of Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City (MIT Press, 2011). Describing the fight for the future of city streets between pedestrians, street railways, and motordom, Fighting Traffic provides a glimpse into the origins of the automotive city.

Starting with a time when city street users were diverse and children played in the streets, Norton describes how pedestrians and parents campaigned in moral terms against “road hogs,” cities and downtown businesses tried to regulate traffic in the name of “efficiency,” and automotive interest groups, legitimized their claim to the streets by invoking “freedom.” He describes how in a bloody, and at times violent revolution, the American city was socially reconstructed by means of motor vehicle codes to become a place dominated by vehicles, not people. By 1930, children no longer belonged on city streets, and pedestrians were condemned as “jaywalkers.”

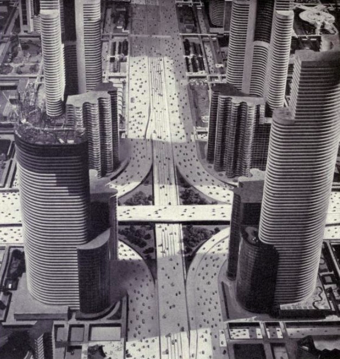

Reinforced by the auto industry through municipal ordinances, the idea dominating city streets is that vehicles are best governed by legal controls and mechanical devices. Highway engineering standards replaced the fact of people in the street with the perception of “modes of traffic.” Worldwide, cities today have vast networks of one-way streets, thousands of miles of traffic dividers, innumerable signals, endless signage, and billions of gallons of paint marking the roads. The 1939 New York World Fair’s Futurama exhibit cemented the notion that modern living and prosperity required traffic and traffic jams.

To engineers, street life is such chaos that they built thousands of miles of hundred-foot-wide paved streets in empty suburbs, and built streets with curbed sidewalks where there are no pedestrians. Their “solutions” to traffic inevitably created new congestion and gridlock and exacerbated the traffic that already exists.3

With traffic now out of control, city blocks everywhere are cluttered with obscene quantities of traffic signs, sometimes occupying 20 percent of the visual field.

Behind the wheel, mellow cariocas, natives of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, drive like screaming banshees, gunning for pedestrians as if with an intent to kill. There, and in the rest of Latin America, in Cairo, Shanghai, Singapore, Dhaka, New Delhi, and Mumbai, huge traffic jams are aggravated by cumbersome systems of one-way streets. Countless signals stop traffic flow at every opportunity.

Lipstick on Pigs

In the absence of workable rules, let alone a general theory, traffic designers design for traffic, and they get traffic. As described in The Art of Classic Planning, new routes invariably become new “problems” as the new resources are overwhelmed and eventually collapse. Then, to fix the damage, we rehire the people who wrought all this havoc in the first place. Well-intentioned planners and engineers continue to threaten that thousands more will die if we do not comply strictly with their guidelines.4

However, trying to generate safety by controlling “dangerous” cars and the “stupid” people driving them has repeatedly failed. Prohibition and segregation of traffic modes instills fear of error in drivers as a modus operandi. Clearly, installing more paving, hardware, and paint is no way to design cities.

Even the so-called ‘Complete Streets’ movement proposes for its streets a cornucopia of geometry, hardware, bump-outs, plastic divider poles, bike boxes at intersections, and other mechanistic devices and markings that either try to make a purse out of a sow’s ear or merely put lipstick on a pig. The author has nothing personal against swine. He simply disagrees with “problem-solving” devices and methods that unilaterally inform people that they are unwelcome on streets, however well-intentioned.5

Classic Streets

Streets in towns, and roads outside them, have to be built in response to genius loci, fabric, and aspiration. For five thousand years, the concept of sharing space with people, animals, and vehicles together has suited the Homo urbanicus. Roman, Spanish, and eighteenth-century planning even legislated this. Classic streets have always strengthened a community’s civic sense and increased opportunities for synergy, rather than fostering inorganic focal places, like big-box malls in the middle of nowhere.

Classic urban spaces elevate the urban experience by intuitively informing all present as to their appropriate behavior. People in classic streets in any mode can calmly, comfortably, and enjoyably negotiate their way with fluidity and freedom.

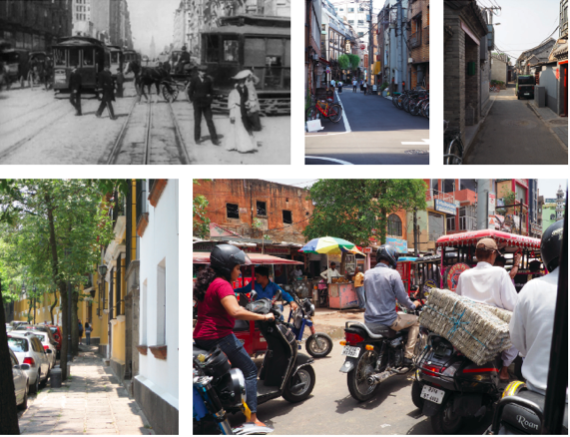

Although last seen in the United States and most of Europe between 1918 and 1945, classic streets are still doing well almost everywhere else in the world. Many streets in Tokyo are classic, though not as a result of outright policy. Almost brought to extinction, hutong neighborhood streets, such as those in Beijing, are lined by traditional courtyard residences which open directly onto the street.

The streets of San Angel Inn, Mexico City are organically classic, as are many streets in Asia and Africa. These streets’ seeming chaos bespeaks not danger but urban vitality. Despite traffic barriers and markings, people in these streets organically insist on occupying and using them as classic streets.6

It is not uncommon to see a driver inching down a one-way road against the direction of traffic. Drivers change lanes, merge, and make turns in traffic heavily laced with pedestrians, trucks, motorized rickshaws, and buses of all sizes, not to mention free-ranging cows in India. They are in reality defensive drivers.

Classic Street Rules

In Africa, Latin America, and Asia, drivers instinctually incorporate the rules of classic streets into their driving. Intuitively, they know that:

Rule #1: Everyone on the street is a person.

Rule #2: Everyone on the street has 100% directional mobility.

Rule #3: Street beauty reduces stress. For best effect detail the street design using traditional, if not classical, design.

Rule #4: Plowed snow shows how much pavement is actually needed.

Rule #5: A safe street is one in which children can play.

Rule #6: A good street has lots of trees.

Although driving in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America may terrify Western drivers and passengers, urban accidents are rare. Most fatalities occur where people can drive unnecessarily fast, places that encourage driving errors. In the ninety cities I visited prior to the publication of my book, I did not see a single accident in Latin America, Asia, or Europe. Drivers in congested areas maintain flow despite signals and signs. The key to properly designing streets for vehicles is intuitive driving.

Notably, Woonerfs, where pedestrians are given priority over cars, are different from classic streets where everyone has equal priority regardless of mode. Obviously, pedestrian-only streets are not classic streets in the fullest sense, although they often emulate their shapes.

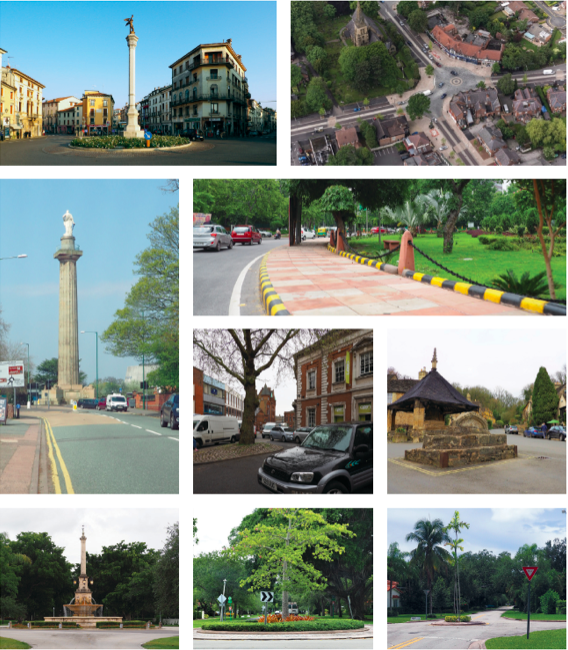

Among the few devices used in classic streets are roundabouts, and their design is an art. Good design makes British rotaries and roundabouts effective—and bad design makes them unpopular in the US. Conducive to the natural flow of traffic, even a small, six-foot diameter painted disc in the middle of an intersection may be enough to properly cue drivers. Driverless cars are particularly well-suited to roundabouts. Designed properly, roundabouts may obviate traffic signage and signaling—and city streets can once again become more humane and classic.

It is easy to conclude that, however well-intentioned, “smart city” and “smart street” initiatives—electronically monitoring thousands of closed-circuit cameras, collecting infinite data from sensors on highways, tunnels, bridges, signs, signals, and lane markings—will not be as safe, durable, or cost-effective as classic streets. In fact, 80 percent of road casualties occur at or within 150 feet (50m) of signalized crossings. Removing the problem might just be more effective than solving it.7

End Notes:

- David Shepardson, U.S. traffic deaths fell in 2019 for third straight year, Reuters (Website), 5 May 2020. See also: WHO, ed., Global Status Report on Road Safety 2018 (PDF), Geneva: World Health Organisation (WHO), pp. xiv–xv, 1–13, 91ff (countries), 302–313 (table A2), 392–397 (table A11), 2018.

- In 2014, 269 people perished in fatal traffic accidents in New York City. See: WNYC, “Mean Streets 2014,” WNYC, https://project.wnyc.org/traffic-deaths/.

- Ben Hamilton-Baillie, English urban designer and traffic planner, is the leader of the Classic Streets movement.

- Susan Handy, California Department of Transportation, “Increasing Highway Capacity Unlikely to Relieve Traffic Congestion,” policy brief, National Center for Sustainable Transportation, November 2015. See also: Olivia Solon, “Elon Musk to Dig Tunnel to Ease Traffic in LA, but He Does Not Yet Have Permission,” Guardian, January 26, 2017.

- Arguably, there is little science or truth in such “bibles” as the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. See: Barbara McCann and Suzanne Rynne, eds., Complete Streets: Best Policy and Implementation Practices, Washington, DC: APA Planning Advisory Service, 2010.

- Miles Brothers, “A Trip Down Market Street before the Fire,” film (Miles Brothers, 1906), Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/item/00694408.

- An adaptive control system developed in Sydney to adjust traffic signals in real time based on driving conditions, demand, and road capacity reduced travel time only 37 percent, congestion by only 21 percent, and carbon dioxide emissions by a mere 6 percent. See: Lauren Drell, “4 Cities Using Tech to Alleviate Traffic,” Mashable, November 16, 2011. The casualty figure is based on five years of UK statistics. See also: Ben Hamilton-Baillie, personal communication, Reported pedestrian casualties by location, age, road crossing type, and severity, Great Britain Department for Transport Statistics, DfT STATS19, 2011–2015, May 10, 2018.

[Classic Planning is a registered trademark of the Nir Buras Entities.]

WELCOME!

Get In Touch

Please get in touch with us

to discuss your requirements.

Please get in touch with us

to discuss your requirements.